Last week, the Bank of England released the result of an independent review of the future of finance, together with its response. As if to prove the importance of these issues, Facebook and 27 partners announced a plan for a global digital currency to be called Libra, and an associated payment system. How should one assess the significance, promise and risks of these developments? How should the regulators react? The answer is: with caution.

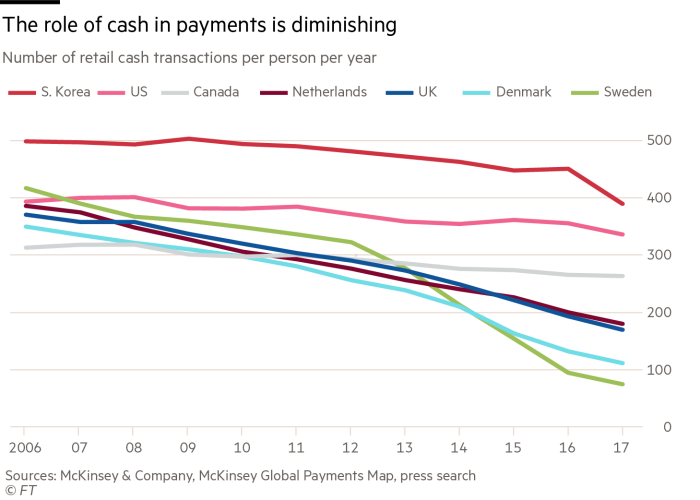

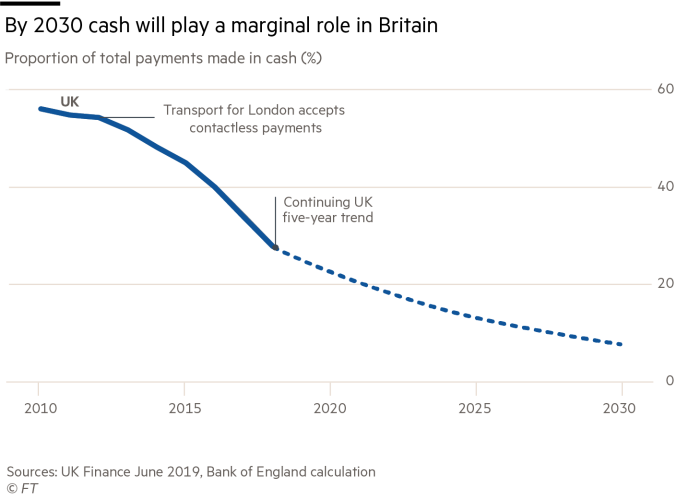

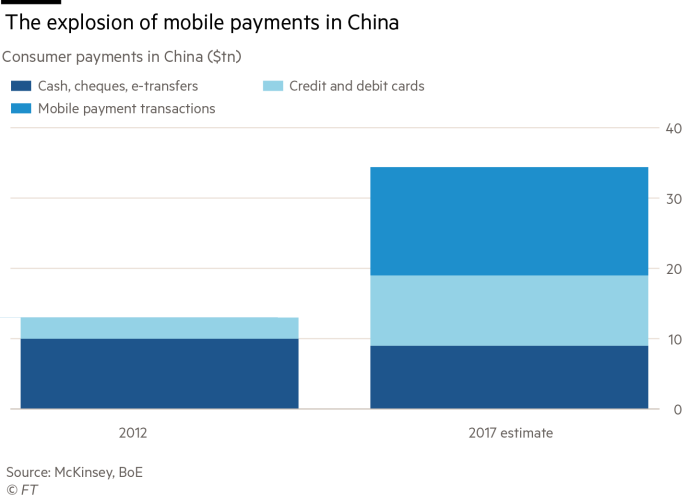

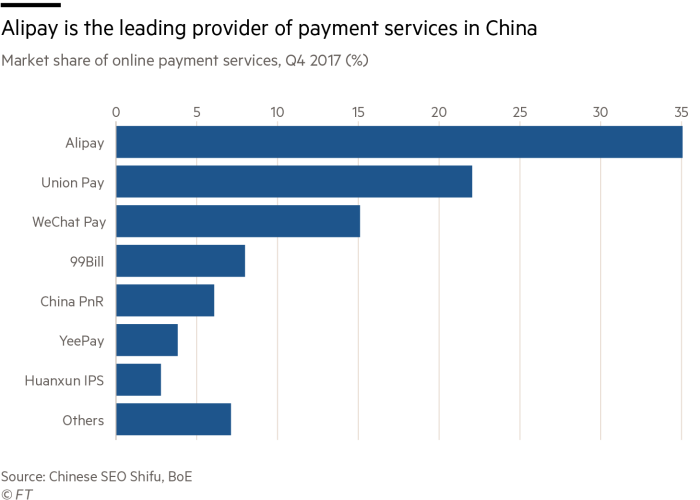

The information revolution, now augmented by artificial intelligence, will surely revolutionise finance. It offers huge potential benefits, in the form of faster and cheaper payments, superior financial services and better risk management. Already, we see a marked decline in the use of cash and explosive growth in digital payments. In China, the revolution in payment technology, led by Alipay (now part of Ant Financial) is extraordinary. Facebook is trying to create a rival. Note: the US is here following China.

Yet finance is also a critical infrastructure. A financial breakdown is likely to create a huge economic crisis. Ill-understood innovation has often proved a midwife of such calamities. It is vital therefore to ensure that the implications of big innovations, such as Libra,are understood. Mark Carney, governor of the BoE, argued last week in his Mansion House speech that the bank “approaches Libra with an open mind but not an open door”. The mind cannot be entirely open, however.

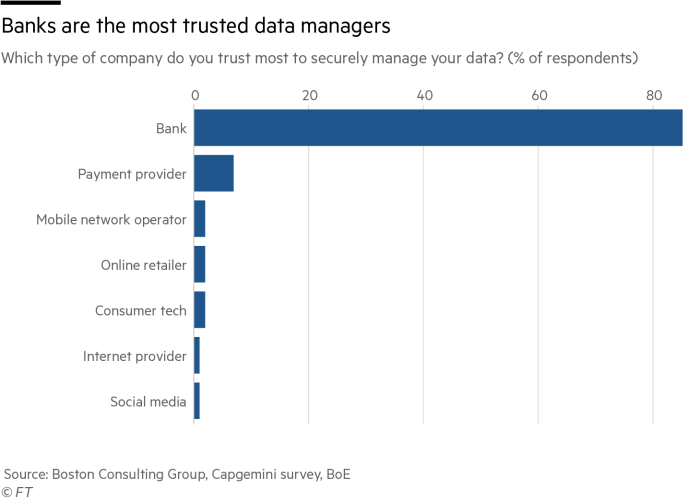

A first question must be whether we can trust the sponsor of so sensitive an innovation. Facebook has been grossly irresponsible over its impact on our democracies. It cannot obviously be trusted with our payments systems. Facebook has an answer: it has just one vote in the Libra Association, which will have independent governance located in Geneva. The aim is to have 100 members by the launch in 2020. But Facebook seems likely to dominate Libra’s technical development. That will surely give it predominant influence.

Randal Quarles, chairman of the Financial Stability Board, is right to tell leaders of the G20 nations, meeting in Japan, that “a wider use of new types of cryptoassets for retail payment purposes would warrant close scrutiny by authorities to ensure that they are subject to high standards of regulation”.

Thus, quite apart from doubts about the sponsor, a new global payment system must be evaluated for its technical stability, impact on monetary and financial stability (not least in developing countries) and openness to fraudsters, criminals and terrorists. Big questions also arise about concentrations of power, should the venture succeed.

Today’s plan is only for a payment system. The currency itself is, in the words of the Libra white paper, to be “fully backed by a reserve of real assets. A basket of bank deposits and short-term government securities will be held in the Libra Reserve for every Libra that is created, building trust in its intrinsic value.” That value will, however, be vulnerable to foreign exchange fluctuations and financial shocks (including exchange controls). Its movements relative to currencies could disturb users. Regulators will have to assess the instabilities associated with such a system.

I cannot judge the technical stability of the proposed system. The claim that it is based on “blockchain” technology seems rather questionable. But only fanatical supporters of “permissionless” systems need worry about that. What matters most is that the system is robust, resistant to breaches and protects personal privacy, while being sufficiently transparent to regulators, judicial authorities and others with a legitimate interest in who uses it.

A crucial issue is how Libra would interact with traditional banks. It might deprive them of a large proportion of their customers, on the payments side. Instead, the Libra system might hold huge deposits in the banks, matched, on the other side of its balance sheets, by customers’ holdings of Libra.

Alternatively, as Mr Carney said: “As new payment providers and systems emerge, access to the [BoE’s] core infrastructure should change and it makes sense to consider whether they too can hold funds overnight on the bank’s balance sheet.” To the extent that central banks create these reserves (a decision they alone make), a system like Libra might circumvent the traditional bank-based payment systems altogether. The historic advantages of banks as informed lenders might disappear.

A far more significant possibility emerges: the Libra system, with its knowledge of customers, would become a lender itself, thereby usurping traditional banks on the asset side of their balance sheets. At worst, the world might have a Facebook-dominated mono-bank. The risks of that are huge: potential monetary and financial instability, concentrated economic and political power, lack of privacy and many other issues. A global currency, created by the lending of a global bank (since banks create money as a byproduct of their loans), in a currency (the Libra) not backed by any central bank, and with no dominant regulator, seems to create a nightmarish risk to stability.

There is indeed potential for greatly improved payment systems. But the emergence of a payment system on a network of Facebook’s scale would raise some huge questions. Should Libra ultimately develop into a true banking system, with the capacity to create its own fiat (man-made) currency, the questions would become yet more pressing. Even if lending by the Libra system is ruled out, regulators should not allow this plan to go ahead without fully understanding the implications. This would be true even if the lead sponsor were not Facebook. But it is. So beware.

Source: Facebook enters dangerous waters with Libra cryptocurrency | Financial Times